Chapter 48 - Being for the Benefit of Mr Vincent Crummles, and positively his lastAppearance on this Stage

It was with a very sad and heavy heart, oppressed by many painful ideas,that Nicholas retraced his steps eastward and betook himself to thecounting-house of Cheeryble Brothers. Whatever the idle hopes he hadsuffered himself to entertain, whatever the pleasant visions which hadsprung up in his mind and grouped themselves round the fair image ofMadeline Bray, they were now dispelled, and not a vestige of theirgaiety and brightness remained.

It would be a poor compliment to Nicholas's better nature, and one whichhe was very far from deserving, to insinuate that the solution, and sucha solution, of the mystery which had seemed to surround Madeline Bray,when he was ignorant even of her name, had damped his ardour or cooledthe fervour of his admiration. If he had regarded her before, withsuch a passion as young men attracted by mere beauty and elegance mayentertain, he was now conscious of much deeper and stronger feelings.But, reverence for the truth and purity of her heart, respect for thehelplessness and loneliness of her situation, sympathy with the trialsof one so young and fair and admiration of her great and noble spirit,all seemed to raise her far above his reach, and, while they impartednew depth and dignity to his love, to whisper that it was hopeless.

'I will keep my word, as I have pledged it to her,' said Nicholas,manfully. 'This is no common trust that I have to discharge, and I willperform the double duty that is imposed upon me most scrupulously andstrictly. My secret feelings deserve no consideration in such a case asthis, and they shall have none.'

Still, there were the secret feelings in existence just the same, and insecret Nicholas rather encouraged them than otherwise; reasoning (ifhe reasoned at all) that there they could do no harm to anybody buthimself, and that if he kept them to himself from a sense of duty, hehad an additional right to entertain himself with them as a reward forhis heroism.

All these thoughts, coupled with what he had seen that morning and theanticipation of his next visit, rendered him a very dull and abstractedcompanion; so much so, indeed, that Tim Linkinwater suspected he musthave made the mistake of a figure somewhere, which was preying upon hismind, and seriously conjured him, if such were the case, to make a cleanbreast and scratch it out, rather than have his whole life embittered bythe tortures of remorse.

But in reply to these considerate representations, and many others bothfrom Tim and Mr Frank, Nicholas could only be brought to state thathe was never merrier in his life; and so went on all day, and so wenttowards home at night, still turning over and over again the samesubjects, thinking over and over again the same things, and arrivingover and over again at the same conclusions.

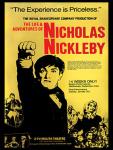

In this pensive, wayward, and uncertain state, people are apt to loungeand loiter without knowing why, to read placards on the walls with greatattention and without the smallest idea of one word of their contents,and to stare most earnestly through shop-windows at things which theydon't see. It was thus that Nicholas found himself poring with theutmost interest over a large play-bill hanging outside a Minor Theatrewhich he had to pass on his way home, and reading a list of the actorsand actresses who had promised to do honour to some approaching benefit,with as much gravity as if it had been a catalogue of the names of thoseladies and gentlemen who stood highest upon the Book of Fate, and he hadbeen looking anxiously for his own. He glanced at the top of the bill,with a smile at his own dulness, as he prepared to resume his walk, andthere saw announced, in large letters with a large space between eachof them, 'Positively the last appearance of Mr Vincent Crummles ofProvincial Celebrity!!!'

'Nonsense!' said Nicholas, turning back again. 'It can't be.'

But there it was. In one line by itself was an announcement of the firstnight of a new melodrama; in another line by itself was an announcementof the last six nights of an old one; a third line was devoted to there-engagement of the unrivalled African Knife-swallower, who had kindlysuffered himself to be prevailed upon to forego his country engagementsfor one week longer; a fourth line announced that Mr Snittle Timberry,having recovered from his late severe indisposition, would have thehonour of appearing that evening; a fifth line said that there were'Cheers, Tears, and Laughter!' every night; a sixth, that that waspositively the last appearance of Mr Vincent Crummles of ProvincialCelebrity.

'Surely it must be the same man,' thought Nicholas. 'There can't be twoVincent Crummleses.'

The better to settle this question he referred to the bill again, andfinding that there was a Baron in the first piece, and that Roberto (hisson) was enacted by one Master Crummles, and Spaletro (his nephew) byone Master Percy Crummles--THEIR last appearances--and that, incidentalto the piece, was a characteristic dance by the characters, and acastanet pas seul by the Infant Phenomenon--HER last appearance--he nolonger entertained any doubt; and presenting himself at the stage-door,and sending in a scrap of paper with 'Mr Johnson' written thereon inpencil, was presently conducted by a Robber, with a very large belt andbuckle round his waist, and very large leather gauntlets on his hands,into the presence of his former manager.

Mr Crummles was unfeignedly glad to see him, and starting up from beforea small dressing-glass, with one very bushy eyebrow stuck on crookedover his left eye, and the fellow eyebrow and the calf of one of hislegs in his hand, embraced him cordially; at the same time observing,that it would do Mrs Crummles's heart good to bid him goodbye beforethey went.

'You were always a favourite of hers, Johnson,' said Crummles, 'alwayswere from the first. I was quite easy in my mind about you from thatfirst day you dined with us. One that Mrs Crummles took a fancy to, wassure to turn out right. Ah! Johnson, what a woman that is!'

'I am sincerely obliged to her for her kindness in this and all otherrespects,' said Nicholas. 'But where are you going, that you talk aboutbidding goodbye?'

'Haven't you seen it in the papers?' said Crummles, with some dignity.

'No,' replied Nicholas.

'I wonder at that,' said the manager. 'It was among the varieties. I hadthe paragraph here somewhere--but I don't know--oh, yes, here it is.'

So saying, Mr Crummles, after pretending that he thought he must havelost it, produced a square inch of newspaper from the pocket of thepantaloons he wore in private life (which, together with the plainclothes of several other gentlemen, lay scattered about on a kind ofdresser in the room), and gave it to Nicholas to read:

'The talented Vincent Crummles, long favourably known to fame as acountry manager and actor of no ordinary pretensions, is about to crossthe Atlantic on a histrionic expedition. Crummles is to be accompanied,we hear, by his lady and gifted family. We know no man superior toCrummles in his particular line of character, or one who, whether as apublic or private individual, could carry with him the best wishes of alarger circle of friends. Crummles is certain to succeed.'

'Here's another bit,' said Mr Crummles, handing over a still smallerscrap. 'This is from the notices to correspondents, this one.'

Nicholas read it aloud. '"Philo-Dramaticus. Crummles, the countrymanager and actor, cannot be more than forty-three, or forty-fouryears of age. Crummles is NOT a Prussian, having been born at Chelsea."Humph!' said Nicholas, 'that's an odd paragraph.'

'Very,' returned Crummles, scratching the side of his nose, and lookingat Nicholas with an assumption of great unconcern. 'I can't think whoputs these things in. I didn't.'

Still keeping his eye on Nicholas, Mr Crummles shook his head twice orthrice with profound gravity, and remarking, that he could not for thelife of him imagine how the newspapers found out the things they did,folded up the extracts and put them in his pocket again.

'I am astonished to hear this news,' said Nicholas. 'Going to America!You had no such thing in contemplation when I was with you.'

'No,' replied Crummles, 'I hadn't then. The fact is that MrsCrummles--most extraordinary woman, Johnson.' Here he broke off andwhispered something in his ear.

'Oh!' said Nicholas, smiling. 'The prospect of an addition to yourfamily?'

'The seventh addition, Johnson,' returned Mr Crummles, solemnly. 'Ithought such a child as the Phenomenon must have been a closer; but itseems we are to have another. She is a very remarkable woman.'

'I congratulate you,' said Nicholas, 'and I hope this may prove aphenomenon too.'

'Why, it's pretty sure to be something uncommon, I suppose,' rejoinedMr Crummles. 'The talent of the other three is principally in combat andserious pantomime. I should like this one to have a turn for juveniletragedy; I understand they want something of that sort in America verymuch. However, we must take it as it comes. Perhaps it may have a geniusfor the tight-rope. It may have any sort of genius, in short, if ittakes after its mother, Johnson, for she is an universal genius; but,whatever its genius is, that genius shall be developed.'

Expressing himself after these terms, Mr Crummles put on his othereyebrow, and the calves of his legs, and then put on his legs, whichwere of a yellowish flesh-colour, and rather soiled about the knees,from frequent going down upon those joints, in curses, prayers, laststruggles, and other strong passages.

While the ex-manager completed his toilet, he informed Nicholas that ashe should have a fair start in America from the proceeds of a tolerablygood engagement which he had been fortunate enough to obtain, and ashe and Mrs Crummles could scarcely hope to act for ever (not beingimmortal, except in the breath of Fame and in a figurative sense) he hadmade up his mind to settle there permanently, in the hope of acquiringsome land of his own which would support them in their old age, andwhich they could afterwards bequeath to their children. Nicholas, havinghighly commended the resolution, Mr Crummles went on to impart suchfurther intelligence relative to their mutual friends as he thoughtmight prove interesting; informing Nicholas, among other things, thatMiss Snevellicci was happily married to an affluent young wax-chandlerwho had supplied the theatre with candles, and that Mr Lillyvick didn'tdare to say his soul was his own, such was the tyrannical sway of MrsLillyvick, who reigned paramount and supreme.

Nicholas responded to this confidence on the part of Mr Crummles, byconfiding to him his own name, situation, and prospects, and informinghim, in as few general words as he could, of the circumstances whichhad led to their first acquaintance. After congratulating him with greatheartiness on the improved state of his fortunes, Mr Crummles gave himto understand that next morning he and his were to start for Liverpool,where the vessel lay which was to carry them from the shores of England,and that if Nicholas wished to take a last adieu of Mrs Crummles, hemust repair with him that night to a farewell supper, given in honour ofthe family at a neighbouring tavern; at which Mr Snittle Timberry wouldpreside, while the honours of the vice-chair would be sustained by theAfrican Swallower.

The room being by this time very warm and somewhat crowded, inconsequence of the influx of four gentlemen, who had just killedeach other in the piece under representation, Nicholas acceptedthe invitation, and promised to return at the conclusion of theperformances; preferring the cool air and twilight out of doors to themingled perfume of gas, orange-peel, and gunpowder, which pervaded thehot and glaring theatre.

He availed himself of this interval to buy a silver snuff-box--the besthis funds would afford--as a token of remembrance for Mr Crummles,and having purchased besides a pair of ear-rings for Mrs Crummles, anecklace for the Phenomenon, and a flaming shirt-pin for each of theyoung gentlemen, he refreshed himself with a walk, and returning alittle after the appointed time, found the lights out, the theatreempty, the curtain raised for the night, and Mr Crummles walking up anddown the stage expecting his arrival.

'Timberry won't be long,' said Mr Crummles. 'He played the audience outtonight. He does a faithful black in the last piece, and it takes him alittle longer to wash himself.'

'A very unpleasant line of character, I should think?' said Nicholas.

'No, I don't know,' replied Mr Crummles; 'it comes off easily enough,and there's only the face and neck. We had a first-tragedy man in ourcompany once, who, when he played Othello, used to black himself allover. But that's feeling a part and going into it as if you meant it; itisn't usual; more's the pity.'

Mr Snittle Timberry now appeared, arm-in-arm with the African Swallower,and, being introduced to Nicholas, raised his hat half a foot, and saidhe was proud to know him. The Swallower said the same, and looked andspoke remarkably like an Irishman.

'I see by the bills that you have been ill, sir,' said Nicholas to MrTimberry. 'I hope you are none the worse for your exertions tonight?'

Mr Timberry, in reply, shook his head with a gloomy air, tapped hischest several times with great significancy, and drawing his cloak moreclosely about him, said, 'But no matter, no matter. Come!'

It is observable that when people upon the stage are in any straitinvolving the very last extremity of weakness and exhaustion, theyinvariably perform feats of strength requiring great ingenuity andmuscular power. Thus, a wounded prince or bandit chief, who is bleedingto death and too faint to move, except to the softest music (and thenonly upon his hands and knees), shall be seen to approach a cottagedoor for aid in such a series of writhings and twistings, and withsuch curlings up of the legs, and such rollings over and over, and suchgettings up and tumblings down again, as could never be achieved saveby a very strong man skilled in posture-making. And so natural did thissort of performance come to Mr Snittle Timberry, that on their way outof the theatre and towards the tavern where the supper was to be holden,he testified the severity of his recent indisposition and its wastingeffects upon the nervous system, by a series of gymnastic performanceswhich were the admiration of all witnesses.

'Why this is indeed a joy I had not looked for!' said Mrs Crummles, whenNicholas was presented.

'Nor I,' replied Nicholas. 'It is by a mere chance that I have thisopportunity of seeing you, although I would have made a great exertionto have availed myself of it.'

'Here is one whom you know,' said Mrs Crummles, thrusting forward thePhenomenon in a blue gauze frock, extensively flounced, and trousersof the same; 'and here another--and another,' presenting the MasterCrummleses. 'And how is your friend, the faithful Digby?'

'Digby!' said Nicholas, forgetting at the instant that this had beenSmike's theatrical name. 'Oh yes. He's quite--what am I saying?--he isvery far from well.'

'How!' exclaimed Mrs Crummles, with a tragic recoil.

'I fear,' said Nicholas, shaking his head, and making an attempt tosmile, 'that your better-half would be more struck with him now thanever.'

'What mean you?' rejoined Mrs Crummles, in her most popular manner.'Whence comes this altered tone?'

'I mean that a dastardly enemy of mine has struck at me through him, andthat while he thinks to torture me, he inflicts on him such agonies ofterror and suspense as--You will excuse me, I am sure,' said Nicholas,checking himself. 'I should never speak of this, and never do, except tothose who know the facts, but for a moment I forgot myself.'

With this hasty apology Nicholas stooped down to salute the Phenomenon,and changed the subject; inwardly cursing his precipitation, and verymuch wondering what Mrs Crummles must think of so sudden an explosion.

That lady seemed to think very little about it, for the supper being bythis time on table, she gave her hand to Nicholas and repaired with astately step to the left hand of Mr Snittle Timberry. Nicholas had thehonour to support her, and Mr Crummles was placed upon the chairman'sright; the Phenomenon and the Master Crummleses sustained the vice.

The company amounted in number to some twenty-five or thirty, beingcomposed of such members of the theatrical profession, then engaged ordisengaged in London, as were numbered among the most intimate friendsof Mr and Mrs Crummles. The ladies and gentlemen were pretty equallybalanced; the expenses of the entertainment being defrayed by thelatter, each of whom had the privilege of inviting one of the former ashis guest.

It was upon the whole a very distinguished party, for independently ofthe lesser theatrical lights who clustered on this occasion roundMr Snittle Timberry, there was a literary gentleman present who haddramatised in his time two hundred and forty-seven novels as fast asthey had come out--some of them faster than they had come out--and whoWAS a literary gentleman in consequence.

This gentleman sat on the left hand of Nicholas, to whom he wasintroduced by his friend the African Swallower, from the bottom of thetable, with a high eulogium upon his fame and reputation.

'I am happy to know a gentleman of such great distinction,' saidNicholas, politely.

'Sir,' replied the wit, 'you're very welcome, I'm sure. The honour isreciprocal, sir, as I usually say when I dramatise a book. Did you everhear a definition of fame, sir?'

'I have heard several,' replied Nicholas, with a smile. 'What is yours?'

'When I dramatise a book, sir,' said the literary gentleman, 'THAT'Sfame. For its author.'

'Oh, indeed!' rejoined Nicholas.

'That's fame, sir,' said the literary gentleman.

'So Richard Turpin, Tom King, and Jerry Abershaw have handed down tofame the names of those on whom they committed their most impudentrobberies?' said Nicholas.

'I don't know anything about that, sir,' answered the literarygentleman.

'Shakespeare dramatised stories which had previously appeared in print,it is true,' observed Nicholas.

'Meaning Bill, sir?' said the literary gentleman. 'So he did. Billwas an adapter, certainly, so he was--and very well he adaptedtoo--considering.'

'I was about to say,' rejoined Nicholas, 'that Shakespeare derived someof his plots from old tales and legends in general circulation; but itseems to me, that some of the gentlemen of your craft, at the presentday, have shot very far beyond him--'

'You're quite right, sir,' interrupted the literary gentleman, leaningback in his chair and exercising his toothpick. 'Human intellect, sir,has progressed since his time, is progressing, will progress.'

'Shot beyond him, I mean,' resumed Nicholas, 'in quite anotherrespect, for, whereas he brought within the magic circle of his genius,traditions peculiarly adapted for his purpose, and turned familiarthings into constellations which should enlighten the world for ages,you drag within the magic circle of your dulness, subjects not at alladapted to the purposes of the stage, and debase as he exalted. Forinstance, you take the uncompleted books of living authors, fresh fromtheir hands, wet from the press, cut, hack, and carve them to the powersand capacities of your actors, and the capability of your theatres,finish unfinished works, hastily and crudely vamp up ideas not yetworked out by their original projector, but which have doubtless costhim many thoughtful days and sleepless nights; by a comparison ofincidents and dialogue, down to the very last word he may have writtena fortnight before, do your utmost to anticipate his plot--all thiswithout his permission, and against his will; and then, to crown thewhole proceeding, publish in some mean pamphlet, an unmeaning farrago ofgarbled extracts from his work, to which your name as author, with thehonourable distinction annexed, of having perpetrated a hundred otheroutrages of the same description. Now, show me the distinction betweensuch pilfering as this, and picking a man's pocket in the street:unless, indeed, it be, that the legislature has a regard forpocket-handkerchiefs, and leaves men's brains, except when they areknocked out by violence, to take care of themselves.'

'Men must live, sir,' said the literary gentleman, shrugging hisshoulders.

'That would be an equally fair plea in both cases,' replied Nicholas;'but if you put it upon that ground, I have nothing more to say, than,that if I were a writer of books, and you a thirsty dramatist, I wouldrather pay your tavern score for six months, large as it might be, thanhave a niche in the Temple of Fame with you for the humblest corner ofmy pedestal, through six hundred generations.'

The conversation threatened to take a somewhat angry tone when it hadarrived thus far, but Mrs Crummles opportunely interposed to preventits leading to any violent outbreak, by making some inquiries of theliterary gentleman relative to the plots of the six new pieces which hehad written by contract to introduce the African Knife-swallower inhis various unrivalled performances. This speedily engaged him in ananimated conversation with that lady, in the interest of which, allrecollection of his recent discussion with Nicholas very quicklyevaporated.

The board being now clear of the more substantial articles of food,and punch, wine, and spirits being placed upon it and handed about, theguests, who had been previously conversing in little groups of threeor four, gradually fell off into a dead silence, while the majority ofthose present glanced from time to time at Mr Snittle Timberry, andthe bolder spirits did not even hesitate to strike the table with theirknuckles, and plainly intimate their expectations, by uttering suchencouragements as 'Now, Tim,' 'Wake up, Mr Chairman,' 'All charged, sir,and waiting for a toast,' and so forth.

To these remonstrances Mr Timberry deigned no other rejoinder thanstriking his chest and gasping for breath, and giving many otherindications of being still the victim of indisposition--for a manmust not make himself too cheap either on the stage or off--whileMr Crummles, who knew full well that he would be the subject of theforthcoming toast, sat gracefully in his chair with his arm throwncarelessly over the back, and now and then lifted his glass to his mouthand drank a little punch, with the same air with which he was accustomedto take long draughts of nothing, out of the pasteboard goblets inbanquet scenes.

At length Mr Snittle Timberry rose in the most approved attitude, withone hand in the breast of his waistcoat and the other on the nearestsnuff-box, and having been received with great enthusiasm, proposed,with abundance of quotations, his friend Mr Vincent Crummles: ending apretty long speech by extending his right hand on one side and his lefton the other, and severally calling upon Mr and Mrs Crummles to graspthe same. This done, Mr Vincent Crummles returned thanks, and that done,the African Swallower proposed Mrs Vincent Crummles, in affecting terms.Then were heard loud moans and sobs from Mrs Crummles and the ladies,despite of which that heroic woman insisted upon returning thanksherself, which she did, in a manner and in a speech which has never beensurpassed and seldom equalled. It then became the duty of Mr SnittleTimberry to give the young Crummleses, which he did; after whichMr Vincent Crummles, as their father, addressed the company in asupplementary speech, enlarging on their virtues, amiabilities, andexcellences, and wishing that they were the sons and daughter of everylady and gentleman present. These solemnities having been succeeded bya decent interval, enlivened by musical and other entertainments,Mr Crummles proposed that ornament of the profession, the AfricanSwallower, his very dear friend, if he would allow him to call him so;which liberty (there being no particular reason why he should not allowit) the African Swallower graciously permitted. The literary gentlemanwas then about to be drunk, but it being discovered that he had beendrunk for some time in another acceptation of the term, and was thenasleep on the stairs, the intention was abandoned, and the honourtransferred to the ladies. Finally, after a very long sitting, MrSnittle Timberry vacated the chair, and the company with many adieux andembraces dispersed.

Nicholas waited to the last to give his little presents. When he hadsaid goodbye all round and came to Mr Crummles, he could not but markthe difference between their present separation and their parting atPortsmouth. Not a jot of his theatrical manner remained; he put out hishand with an air which, if he could have summoned it at will, would havemade him the best actor of his day in homely parts, and when Nicholasshook it with the warmth he honestly felt, appeared thoroughly melted.

'We were a very happy little company, Johnson,' said poor Crummles. 'Youand I never had a word. I shall be very glad tomorrow morning to thinkthat I saw you again, but now I almost wish you hadn't come.'

Nicholas was about to return a cheerful reply, when he was greatlydisconcerted by the sudden apparition of Mrs Grudden, who it seemed haddeclined to attend the supper in order that she might rise earlier inthe morning, and who now burst out of an adjoining bedroom, habited invery extraordinary white robes; and throwing her arms about his neck,hugged him with great affection.

'What! Are you going too?' said Nicholas, submitting with as good agrace as if she had been the finest young creature in the world.

'Going?' returned Mrs Grudden. 'Lord ha' mercy, what do you think they'ddo without me?'

Nicholas submitted to another hug with even a better grace than before,if that were possible, and waving his hat as cheerfully as he could,took farewell of the Vincent Crummleses.