Chapter 22 - Nicholas, accompanied by Smike, sallies forth to seek his Fortune. Heencounters Mr Vincent Crummles; and who he was, is herein made manifest

The whole capital which Nicholas found himself entitled to, either inpossession, reversion, remainder, or expectancy, after paying his rentand settling with the broker from whom he had hired his poor furniture,did not exceed, by more than a few halfpence, the sum of twentyshillings. And yet he hailed the morning on which he had resolvedto quit London, with a light heart, and sprang from his bed with anelasticity of spirit which is happily the lot of young persons, or theworld would never be stocked with old ones.

It was a cold, dry, foggy morning in early spring. A few meagre shadowsflitted to and fro in the misty streets, and occasionally there loomedthrough the dull vapour, the heavy outline of some hackney coach wendinghomewards, which, drawing slowly nearer, rolled jangling by, scatteringthe thin crust of frost from its whitened roof, and soon was lost againin the cloud. At intervals were heard the tread of slipshod feet, andthe chilly cry of the poor sweep as he crept, shivering, to his earlytoil; the heavy footfall of the official watcher of the night, pacingslowly up and down and cursing the tardy hours that still intervenedbetween him and sleep; the rambling of ponderous carts and waggons; theroll of the lighter vehicles which carried buyers and sellers to thedifferent markets; the sound of ineffectual knocking at the doors ofheavy sleepers--all these noises fell upon the ear from time totime, but all seemed muffled by the fog, and to be rendered almost asindistinct to the ear as was every object to the sight. The sluggishdarkness thickened as the day came on; and those who had the courage torise and peep at the gloomy street from their curtained windows, creptback to bed again, and coiled themselves up to sleep.

Before even these indications of approaching morning were rife in busyLondon, Nicholas had made his way alone to the city, and stood beneaththe windows of his mother's house. It was dull and bare to see, but ithad light and life for him; for there was at least one heart withinits old walls to which insult or dishonour would bring the same bloodrushing, that flowed in his own veins.

He crossed the road, and raised his eyes to the window of the room wherehe knew his sister slept. It was closed and dark. 'Poor girl,' thoughtNicholas, 'she little thinks who lingers here!'

He looked again, and felt, for the moment, almost vexed that Kate wasnot there to exchange one word at parting. 'Good God!' he thought,suddenly correcting himself, 'what a boy I am!'

'It is better as it is,' said Nicholas, after he had lounged on, a fewpaces, and returned to the same spot. 'When I left them before, andcould have said goodbye a thousand times if I had chosen, I spared themthe pain of leave-taking, and why not now?' As he spoke, some fanciedmotion of the curtain almost persuaded him, for the instant, that Katewas at the window, and by one of those strange contradictions of feelingwhich are common to us all, he shrunk involuntarily into a doorway, thatshe might not see him. He smiled at his own weakness; said 'God blessthem!' and walked away with a lighter step.

Smike was anxiously expecting him when he reached his old lodgings, andso was Newman, who had expended a day's income in a can of rum and milkto prepare them for the journey. They had tied up the luggage, Smikeshouldered it, and away they went, with Newman Noggs in company; for hehad insisted on walking as far as he could with them, overnight.

'Which way?' asked Newman, wistfully.

'To Kingston first,' replied Nicholas.

'And where afterwards?' asked Newman. 'Why won't you tell me?'

'Because I scarcely know myself, good friend,' rejoined Nicholas, layinghis hand upon his shoulder; 'and if I did, I have neither plan norprospect yet, and might shift my quarters a hundred times before youcould possibly communicate with me.'

'I am afraid you have some deep scheme in your head,' said Newman,doubtfully.

'So deep,' replied his young friend, 'that even I can't fathom it.Whatever I resolve upon, depend upon it I will write you soon.'

'You won't forget?' said Newman.

'I am not very likely to,' rejoined Nicholas. 'I have not so manyfriends that I shall grow confused among the number, and forget my bestone.'

Occupied in such discourse, they walked on for a couple of hours,as they might have done for a couple of days if Nicholas had not sathimself down on a stone by the wayside, and resolutely declared hisintention of not moving another step until Newman Noggs turned back.Having pleaded ineffectually first for another half-mile, and afterwardsfor another quarter, Newman was fain to comply, and to shape his coursetowards Golden Square, after interchanging many hearty and affectionatefarewells, and many times turning back to wave his hat to the twowayfarers when they had become mere specks in the distance.

'Now listen to me, Smike,' said Nicholas, as they trudged with stouthearts onwards. 'We are bound for Portsmouth.'

Smike nodded his head and smiled, but expressed no other emotion; forwhether they had been bound for Portsmouth or Port Royal would have beenalike to him, so they had been bound together.

'I don't know much of these matters,' resumed Nicholas; 'but Portsmouthis a seaport town, and if no other employment is to be obtained, Ishould think we might get on board some ship. I am young and active, andcould be useful in many ways. So could you.'

'I hope so,' replied Smike. 'When I was at that--you know where I mean?'

'Yes, I know,' said Nicholas. 'You needn't name the place.'

'Well, when I was there,' resumed Smike; his eyes sparkling at theprospect of displaying his abilities; 'I could milk a cow, and groom ahorse, with anybody.'

'Ha!' said Nicholas, gravely. 'I am afraid they don't keep many animalsof either kind on board ship, Smike, and even when they have horses,that they are not very particular about rubbing them down; still you canlearn to do something else, you know. Where there's a will, there's away.'

'And I am very willing,' said Smike, brightening up again.

'God knows you are,' rejoined Nicholas; 'and if you fail, it shall gohard but I'll do enough for us both.'

'Do we go all the way today?' asked Smike, after a short silence.

'That would be too severe a trial, even for your willing legs,' saidNicholas, with a good-humoured smile. 'No. Godalming is some thirty andodd miles from London--as I found from a map I borrowed--and I purposeto rest there. We must push on again tomorrow, for we are not richenough to loiter. Let me relieve you of that bundle! Come!'

'No, no,' rejoined Smike, falling back a few steps. 'Don't ask me togive it up to you.'

'Why not?' asked Nicholas.

'Let me do something for you, at least,' said Smike. 'You will never letme serve you as I ought. You will never know how I think, day and night,of ways to please you.'

'You are a foolish fellow to say it, for I know it well, and see it, orI should be a blind and senseless beast,' rejoined Nicholas. 'Let me askyou a question while I think of it, and there is no one by,' he added,looking him steadily in the face. 'Have you a good memory?'

'I don't know,' said Smike, shaking his head sorrowfully. 'I think I hadonce; but it's all gone now--all gone.'

'Why do you think you had once?' asked Nicholas, turning quickly uponhim as though the answer in some way helped out the purport of hisquestion.

'Because I could remember, when I was a child,' said Smike, 'but that isvery, very long ago, or at least it seems so. I was always confusedand giddy at that place you took me from; and could never remember,and sometimes couldn't even understand, what they said to me. I--let mesee--let me see!'

'You are wandering now,' said Nicholas, touching him on the arm.

'No,' replied his companion, with a vacant look 'I was only thinkinghow--' He shivered involuntarily as he spoke.

'Think no more of that place, for it is all over,' retorted Nicholas,fixing his eyes full upon that of his companion, which was fast settlinginto an unmeaning stupefied gaze, once habitual to him, and common eventhen. 'What of the first day you went to Yorkshire?'

'Eh!' cried the lad.

'That was before you began to lose your recollection, you know,' saidNicholas quietly. 'Was the weather hot or cold?'

'Wet,' replied the boy. 'Very wet. I have always said, when it hasrained hard, that it was like the night I came: and they used to crowdround and laugh to see me cry when the rain fell heavily. It was like achild, they said, and that made me think of it more. I turned cold allover sometimes, for I could see myself as I was then, coming in at thevery same door.'

'As you were then,' repeated Nicholas, with assumed carelessness; 'howwas that?'

'Such a little creature,' said Smike, 'that they might have had pity andmercy upon me, only to remember it.'

'You didn't find your way there, alone!' remarked Nicholas.

'No,' rejoined Smike, 'oh no.'

'Who was with you?'

'A man--a dark, withered man. I have heard them say so, at the school,and I remembered that before. I was glad to leave him, I was afraid ofhim; but they made me more afraid of them, and used me harder too.'

'Look at me,' said Nicholas, wishing to attract his full attention.'There; don't turn away. Do you remember no woman, no kind woman, whohung over you once, and kissed your lips, and called you her child?'

'No,' said the poor creature, shaking his head, 'no, never.'

'Nor any house but that house in Yorkshire?'

'No,' rejoined the youth, with a melancholy look; 'a room--I rememberI slept in a room, a large lonesome room at the top of a house, wherethere was a trap-door in the ceiling. I have covered my head with theclothes often, not to see it, for it frightened me: a young child withno one near at night: and I used to wonder what was on the other side.There was a clock too, an old clock, in one corner. I remember that.I have never forgotten that room; for when I have terrible dreams, itcomes back, just as it was. I see things and people in it that I hadnever seen then, but there is the room just as it used to be; THAT neverchanges.'

'Will you let me take the bundle now?' asked Nicholas, abruptly changingthe theme.

'No,' said Smike, 'no. Come, let us walk on.'

He quickened his pace as he said this, apparently under the impressionthat they had been standing still during the whole of the previousdialogue. Nicholas marked him closely, and every word of thisconversation remained upon his memory.

It was, by this time, within an hour of noon, and although a densevapour still enveloped the city they had left, as if the very breath ofits busy people hung over their schemes of gain and profit, and foundgreater attraction there than in the quiet region above, in the opencountry it was clear and fair. Occasionally, in some low spots theycame upon patches of mist which the sun had not yet driven from theirstrongholds; but these were soon passed, and as they laboured up thehills beyond, it was pleasant to look down, and see how the sluggishmass rolled heavily off, before the cheering influence of day. A broad,fine, honest sun lighted up the green pastures and dimpled waterwith the semblance of summer, while it left the travellers all theinvigorating freshness of that early time of year. The ground seemedelastic under their feet; the sheep-bells were music to their ears; andexhilarated by exercise, and stimulated by hope, they pushed onward withthe strength of lions.

The day wore on, and all these bright colours subsided, and assumeda quieter tint, like young hopes softened down by time, or youthfulfeatures by degrees resolving into the calm and serenity of age. Butthey were scarcely less beautiful in their slow decline, than they hadbeen in their prime; for nature gives to every time and season somebeauties of its own; and from morning to night, as from the cradle tothe grave, is but a succession of changes so gentle and easy, that wecan scarcely mark their progress.

To Godalming they came at last, and here they bargained for two humblebeds, and slept soundly. In the morning they were astir: thoughnot quite so early as the sun: and again afoot; if not with all thefreshness of yesterday, still, with enough of hope and spirit to bearthem cheerily on.

It was a harder day's journey than yesterday's, for there were long andweary hills to climb; and in journeys, as in life, it is a great dealeasier to go down hill than up. However, they kept on, with unabatedperseverance, and the hill has not yet lifted its face to heaven thatperseverance will not gain the summit of at last.

They walked upon the rim of the Devil's Punch Bowl; and Smike listenedwith greedy interest as Nicholas read the inscription upon the stonewhich, reared upon that wild spot, tells of a murder committed there bynight. The grass on which they stood, had once been dyed with gore;and the blood of the murdered man had run down, drop by drop, intothe hollow which gives the place its name. 'The Devil's Bowl,' thoughtNicholas, as he looked into the void, 'never held fitter liquor thanthat!'

Onward they kept, with steady purpose, and entered at length upon a wideand spacious tract of downs, with every variety of little hill andplain to change their verdant surface. Here, there shot up, almostperpendicularly, into the sky, a height so steep, as to be hardlyaccessible to any but the sheep and goats that fed upon its sides, andthere, stood a mound of green, sloping and tapering off so delicately,and merging so gently into the level ground, that you could scarcedefine its limits. Hills swelling above each other; and undulationsshapely and uncouth, smooth and rugged, graceful and grotesque, thrownnegligently side by side, bounded the view in each direction; whilefrequently, with unexpected noise, there uprose from the ground aflight of crows, who, cawing and wheeling round the nearest hills, as ifuncertain of their course, suddenly poised themselves upon the wing andskimmed down the long vista of some opening valley, with the speed oflight itself.

By degrees, the prospect receded more and more on either hand, and asthey had been shut out from rich and extensive scenery, so they emergedonce again upon the open country. The knowledge that they were drawingnear their place of destination, gave them fresh courage to proceed; butthe way had been difficult, and they had loitered on the road, and Smikewas tired. Thus, twilight had already closed in, when they turnedoff the path to the door of a roadside inn, yet twelve miles short ofPortsmouth.

'Twelve miles,' said Nicholas, leaning with both hands on his stick, andlooking doubtfully at Smike.

'Twelve long miles,' repeated the landlord.

'Is it a good road?' inquired Nicholas.

'Very bad,' said the landlord. As of course, being a landlord, he wouldsay.

'I want to get on,' observed Nicholas, hesitating. 'I scarcely know whatto do.'

'Don't let me influence you,' rejoined the landlord. 'I wouldn't go onif it was me.'

'Wouldn't you?' asked Nicholas, with the same uncertainty.

'Not if I knew when I was well off,' said the landlord. And having saidit he pulled up his apron, put his hands into his pockets, and, takinga step or two outside the door, looked down the dark road with anassumption of great indifference.

A glance at the toil-worn face of Smike determined Nicholas, so withoutany further consideration he made up his mind to stay where he was.

The landlord led them into the kitchen, and as there was a good fire heremarked that it was very cold. If there had happened to be a bad one hewould have observed that it was very warm.

'What can you give us for supper?' was Nicholas's natural question.

'Why--what would you like?' was the landlord's no less natural answer.

Nicholas suggested cold meat, but there was no cold meat--poached eggs,but there were no eggs--mutton chops, but there wasn't a mutton chopwithin three miles, though there had been more last week than they knewwhat to do with, and would be an extraordinary supply the day aftertomorrow.

'Then,' said Nicholas, 'I must leave it entirely to you, as I would havedone, at first, if you had allowed me.'

'Why, then I'll tell you what,' rejoined the landlord. 'There's agentleman in the parlour that's ordered a hot beef-steak pudding andpotatoes, at nine. There's more of it than he can manage, and I havevery little doubt that if I ask leave, you can sup with him. I'll dothat, in a minute.'

'No, no,' said Nicholas, detaining him. 'I would rather not. I--atleast--pshaw! why cannot I speak out? Here; you see that I am travellingin a very humble manner, and have made my way hither on foot. It is morethan probable, I think, that the gentleman may not relish my company;and although I am the dusty figure you see, I am too proud to thrustmyself into his.'

'Lord love you,' said the landlord, 'it's only Mr Crummles; HE isn'tparticular.'

'Is he not?' asked Nicholas, on whose mind, to tell the truth, theprospect of the savoury pudding was making some impression.

'Not he,' replied the landlord. 'He'll like your way of talking, I know.But we'll soon see all about that. Just wait a minute.'

The landlord hurried into the parlour, without staying for furtherpermission, nor did Nicholas strive to prevent him: wisely consideringthat supper, under the circumstances, was too serious a matter to betrifled with. It was not long before the host returned, in a conditionof much excitement.

'All right,' he said in a low voice. 'I knew he would. You'll seesomething rather worth seeing, in there. Ecod, how they are a-going ofit!'

There was no time to inquire to what this exclamation, which wasdelivered in a very rapturous tone, referred; for he had already thrownopen the door of the room; into which Nicholas, followed by Smike withthe bundle on his shoulder (he carried it about with him as vigilantlyas if it had been a sack of gold), straightway repaired.

Nicholas was prepared for something odd, but not for something quite soodd as the sight he encountered. At the upper end of the room, were acouple of boys, one of them very tall and the other very short, bothdressed as sailors--or at least as theatrical sailors, with belts,buckles, pigtails, and pistols complete--fighting what is called inplay-bills a terrific combat, with two of those short broad-swords withbasket hilts which are commonly used at our minor theatres. The shortboy had gained a great advantage over the tall boy, who was reduced tomortal strait, and both were overlooked by a large heavy man, perchedagainst the corner of a table, who emphatically adjured them to strike alittle more fire out of the swords, and they couldn't fail to bring thehouse down, on the very first night.

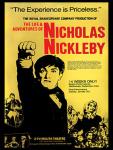

'Mr Vincent Crummles,' said the landlord with an air of great deference.'This is the young gentleman.'

Mr Vincent Crummles received Nicholas with an inclination of the head,something between the courtesy of a Roman emperor and the nod of a potcompanion; and bade the landlord shut the door and begone.

'There's a picture,' said Mr Crummles, motioning Nicholas not to advanceand spoil it. 'The little 'un has him; if the big 'un doesn't knockunder, in three seconds, he's a dead man. Do that again, boys.'

The two combatants went to work afresh, and chopped away until theswords emitted a shower of sparks: to the great satisfaction of MrCrummles, who appeared to consider this a very great point indeed. Theengagement commenced with about two hundred chops administered by theshort sailor and the tall sailor alternately, without producing anyparticular result, until the short sailor was chopped down on one knee;but this was nothing to him, for he worked himself about on the one kneewith the assistance of his left hand, and fought most desperately untilthe tall sailor chopped his sword out of his grasp. Now, the inferencewas, that the short sailor, reduced to this extremity, would give in atonce and cry quarter, but, instead of that, he all of a sudden drewa large pistol from his belt and presented it at the face of the tallsailor, who was so overcome at this (not expecting it) that he letthe short sailor pick up his sword and begin again. Then, the choppingrecommenced, and a variety of fancy chops were administered on bothsides; such as chops dealt with the left hand, and under the leg, andover the right shoulder, and over the left; and when the short sailormade a vigorous cut at the tall sailor's legs, which would have shavedthem clean off if it had taken effect, the tall sailor jumped over theshort sailor's sword, wherefore to balance the matter, and make it allfair, the tall sailor administered the same cut, and the short sailorjumped over HIS sword. After this, there was a good deal of dodgingabout, and hitching up of the inexpressibles in the absence of braces,and then the short sailor (who was the moral character evidently, for healways had the best of it) made a violent demonstration and closed withthe tall sailor, who, after a few unavailing struggles, went down,and expired in great torture as the short sailor put his foot upon hisbreast, and bored a hole in him through and through.

'That'll be a double ENCORE if you take care, boys,' said Mr Crummles.'You had better get your wind now and change your clothes.'

Having addressed these words to the combatants, he saluted Nicholas, whothen observed that the face of Mr Crummles was quite proportionate insize to his body; that he had a very full under-lip, a hoarse voice, asthough he were in the habit of shouting very much, and very shortblack hair, shaved off nearly to the crown of his head--to admit (ashe afterwards learnt) of his more easily wearing character wigs of anyshape or pattern.

'What did you think of that, sir?' inquired Mr Crummles.

'Very good, indeed--capital,' answered Nicholas.

'You won't see such boys as those very often, I think,' said MrCrummles.

Nicholas assented--observing that if they were a little better match--

'Match!' cried Mr Crummles.

'I mean if they were a little more of a size,' said Nicholas, explaininghimself.

'Size!' repeated Mr Crummles; 'why, it's the essence of the combat thatthere should be a foot or two between them. How are you to get up thesympathies of the audience in a legitimate manner, if there isn't alittle man contending against a big one?--unless there's at least fiveto one, and we haven't hands enough for that business in our company.'

'I see,' replied Nicholas. 'I beg your pardon. That didn't occur to me,I confess.'

'It's the main point,' said Mr Crummles. 'I open at Portsmouth the dayafter tomorrow. If you're going there, look into the theatre, and seehow that'll tell.'

Nicholas promised to do so, if he could, and drawing a chair near thefire, fell into conversation with the manager at once. He was verytalkative and communicative, stimulated perhaps, not only by his naturaldisposition, but by the spirits and water he sipped very plentifully, orthe snuff he took in large quantities from a piece of whitey-brown paperin his waistcoat pocket. He laid open his affairs without the smallestreserve, and descanted at some length upon the merits of his company,and the acquirements of his family; of both of which, the twobroad-sword boys formed an honourable portion. There was to bea gathering, it seemed, of the different ladies and gentlemen atPortsmouth on the morrow, whither the father and sons were proceeding(not for the regular season, but in the course of a wanderingspeculation), after fulfilling an engagement at Guildford with thegreatest applause.

'You are going that way?' asked the manager.

'Ye-yes,' said Nicholas. 'Yes, I am.'

'Do you know the town at all?' inquired the manager, who seemed toconsider himself entitled to the same degree of confidence as he hadhimself exhibited.

'No,' replied Nicholas.

'Never there?'

'Never.'

Mr Vincent Crummles gave a short dry cough, as much as to say, 'If youwon't be communicative, you won't;' and took so many pinches of snufffrom the piece of paper, one after another, that Nicholas quite wonderedwhere it all went to.

While he was thus engaged, Mr Crummles looked, from time to time, withgreat interest at Smike, with whom he had appeared considerably struckfrom the first. He had now fallen asleep, and was nodding in his chair.

'Excuse my saying so,' said the manager, leaning over to Nicholas, andsinking his voice, 'but what a capital countenance your friend has got!'

'Poor fellow!' said Nicholas, with a half-smile, 'I wish it were alittle more plump, and less haggard.'

'Plump!' exclaimed the manager, quite horrified, 'you'd spoil it forever.'

'Do you think so?'

'Think so, sir! Why, as he is now,' said the manager, striking his kneeemphatically; 'without a pad upon his body, and hardly a touch of paintupon his face, he'd make such an actor for the starved business as wasnever seen in this country. Only let him be tolerably well up in theApothecary in Romeo and Juliet, with the slightest possible dab of redon the tip of his nose, and he'd be certain of three rounds the momenthe put his head out of the practicable door in the front grooves O.P.'

'You view him with a professional eye,' said Nicholas, laughing.

'And well I may,' rejoined the manager. 'I never saw a young fellow soregularly cut out for that line, since I've been in the profession. AndI played the heavy children when I was eighteen months old.'

The appearance of the beef-steak pudding, which came in simultaneouslywith the junior Vincent Crummleses, turned the conversation to othermatters, and indeed, for a time, stopped it altogether. These two younggentlemen wielded their knives and forks with scarcely less address thantheir broad-swords, and as the whole party were quite as sharp set aseither class of weapons, there was no time for talking until the supperhad been disposed of.

The Master Crummleses had no sooner swallowed the last procurablemorsel of food, than they evinced, by various half-suppressed yawns andstretchings of their limbs, an obvious inclination to retire for thenight, which Smike had betrayed still more strongly: he having, in thecourse of the meal, fallen asleep several times while in the very act ofeating. Nicholas therefore proposed that they should break up atonce, but the manager would by no means hear of it; vowing that he hadpromised himself the pleasure of inviting his new acquaintance toshare a bowl of punch, and that if he declined, he should deem it veryunhandsome behaviour.

'Let them go,' said Mr Vincent Crummles, 'and we'll have it snugly andcosily together by the fire.'

Nicholas was not much disposed to sleep--being in truth too anxious--so,after a little demur, he accepted the offer, and having exchanged ashake of the hand with the young Crummleses, and the manager havingon his part bestowed a most affectionate benediction on Smike, he sathimself down opposite to that gentleman by the fireside to assist inemptying the bowl, which soon afterwards appeared, steaming in amanner which was quite exhilarating to behold, and sending forth a mostgrateful and inviting fragrance.

But, despite the punch and the manager, who told a variety of stories,and smoked tobacco from a pipe, and inhaled it in the shape of snuff,with a most astonishing power, Nicholas was absent and dispirited. Histhoughts were in his old home, and when they reverted to his presentcondition, the uncertainty of the morrow cast a gloom upon him, whichhis utmost efforts were unable to dispel. His attention wandered;although he heard the manager's voice, he was deaf to what he said; andwhen Mr Vincent Crummles concluded the history of some long adventurewith a loud laugh, and an inquiry what Nicholas would have done underthe same circumstances, he was obliged to make the best apology in hispower, and to confess his entire ignorance of all he had been talkingabout.

'Why, so I saw,' observed Mr Crummles. 'You're uneasy in your mind.What's the matter?'

Nicholas could not refrain from smiling at the abruptness of thequestion; but, thinking it scarcely worth while to parry it, owned thathe was under some apprehensions lest he might not succeed in the objectwhich had brought him to that part of the country.

'And what's that?' asked the manager.

'Getting something to do which will keep me and my poor fellow-travellerin the common necessaries of life,' said Nicholas. 'That's the truth.You guessed it long ago, I dare say, so I may as well have the credit oftelling it you with a good grace.'

'What's to be got to do at Portsmouth more than anywhere else?' asked MrVincent Crummles, melting the sealing-wax on the stem of his pipe in thecandle, and rolling it out afresh with his little finger.

'There are many vessels leaving the port, I suppose,' replied Nicholas.'I shall try for a berth in some ship or other. There is meat and drinkthere at all events.'

'Salt meat and new rum; pease-pudding and chaff-biscuits,' said themanager, taking a whiff at his pipe to keep it alight, and returning tohis work of embellishment.

'One may do worse than that,' said Nicholas. 'I can rough it, I believe,as well as most young men of my age and previous habits.'

'You need be able to,' said the manager, 'if you go on board ship; butyou won't.'

'Why not?'

'Because there's not a skipper or mate that would think you worth yoursalt, when he could get a practised hand,' replied the manager; 'andthey as plentiful there, as the oysters in the streets.'

'What do you mean?' asked Nicholas, alarmed by this prediction, andthe confident tone in which it had been uttered. 'Men are not born ableseamen. They must be reared, I suppose?'

Mr Vincent Crummles nodded his head. 'They must; but not at your age, orfrom young gentlemen like you.'

There was a pause. The countenance of Nicholas fell, and he gazedruefully at the fire.

'Does no other profession occur to you, which a young man of your figureand address could take up easily, and see the world to advantage in?'asked the manager.

'No,' said Nicholas, shaking his head.

'Why, then, I'll tell you one,' said Mr Crummles, throwing his pipe intothe fire, and raising his voice. 'The stage.'

'The stage!' cried Nicholas, in a voice almost as loud.

'The theatrical profession,' said Mr Vincent Crummles. 'I am in thetheatrical profession myself, my wife is in the theatrical profession,my children are in the theatrical profession. I had a dog that livedand died in it from a puppy; and my chaise-pony goes on, in Timour theTartar. I'll bring you out, and your friend too. Say the word. I want anovelty.'

'I don't know anything about it,' rejoined Nicholas, whose breath hadbeen almost taken away by this sudden proposal. 'I never acted a part inmy life, except at school.'

'There's genteel comedy in your walk and manner, juvenile tragedyin your eye, and touch-and-go farce in your laugh,' said Mr VincentCrummles. 'You'll do as well as if you had thought of nothing else butthe lamps, from your birth downwards.'

Nicholas thought of the small amount of small change that would remainin his pocket after paying the tavern bill; and he hesitated.

'You can be useful to us in a hundred ways,' said Mr Crummles.'Think what capital bills a man of your education could write for theshop-windows.'

'Well, I think I could manage that department,' said Nicholas.

'To be sure you could,' replied Mr Crummles. '"For further particularssee small hand-bills"--we might have half a volume in every one of'em. Pieces too; why, you could write us a piece to bring out the wholestrength of the company, whenever we wanted one.'

'I am not quite so confident about that,' replied Nicholas. 'But I daresay I could scribble something now and then, that would suit you.'

'We'll have a new show-piece out directly,' said the manager. 'Letme see--peculiar resources of this establishment--new and splendidscenery--you must manage to introduce a real pump and two washing-tubs.'

'Into the piece?' said Nicholas.

'Yes,' replied the manager. 'I bought 'em cheap, at a sale the otherday, and they'll come in admirably. That's the London plan. They look upsome dresses, and properties, and have a piece written to fit 'em. Mostof the theatres keep an author on purpose.'

'Indeed!' cried Nicholas.

'Oh, yes,' said the manager; 'a common thing. It'll look very wellin the bills in separate lines--Real pump!--Splendid tubs!--Greatattraction! You don't happen to be anything of an artist, do you?'

'That is not one of my accomplishments,' rejoined Nicholas.

'Ah! Then it can't be helped,' said the manager. 'If you had been,we might have had a large woodcut of the last scene for the posters,showing the whole depth of the stage, with the pump and tubs in themiddle; but, however, if you're not, it can't be helped.'

'What should I get for all this?' inquired Nicholas, after a fewmoments' reflection. 'Could I live by it?'

'Live by it!' said the manager. 'Like a prince! With your own salary,and your friend's, and your writings, you'd make--ah! you'd make a pounda week!'

'You don't say so!'

'I do indeed, and if we had a run of good houses, nearly double themoney.'

Nicholas shrugged his shoulders; but sheer destitution was before him;and if he could summon fortitude to undergo the extremes of want andhardship, for what had he rescued his helpless charge if it were only tobear as hard a fate as that from which he had wrested him? It was easyto think of seventy miles as nothing, when he was in the same town withthe man who had treated him so ill and roused his bitterest thoughts;but now, it seemed far enough. What if he went abroad, and his mother orKate were to die the while?

Without more deliberation, he hastily declared that it was a bargain,and gave Mr Vincent Crummles his hand upon it.