Chapter 15

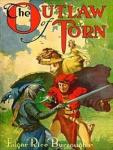

When word of the death of Joan de Tany reached Torn, no man could tell fromoutward appearance the depth of the suffering which the sad intelligencewrought on the master of Torn.

All that they who followed him knew was that certain unusual orders wereissued, and that that same night, the ten companies rode south toward Essexwithout other halt than for necessary food and water for man and beast.

When the body of Joan de Tany rode forth from her father's castle to thechurch at Colchester, and again as it was brought back to its final restingplace in the castle's crypt, a thousand strange and silent knights, blackdraped, upon horses trapped in black, rode slowly behind the bier.

Silently they had come in the night preceding the funeral, and as silently,they slipped away northward into the falling shadows of the followingnight.

No word had passed between those of the castle and the great troop ofsable-clad warriors, but all within knew that the mighty Outlaw of Torn hadcome to pay homage to the memory of the daughter of De Tany, and all butthe grieving mother wondered at the strangeness of the act.

As the horde of Torn approached their Derby stronghold, their young leaderturned the command over to Red Shandy and dismounted at the door of FatherClaude's cottage.

"I am tired, Father," said the outlaw as he threw himself upon hisaccustomed bench. "Naught but sorrow and death follow in my footsteps. Iand all my acts be accurst, and upon those I love, the blight falleth."

"Alter thy ways, my son; follow my advice ere it be too late. Seek out anew and better life in another country and carve thy future into thesemblance of glory and honor."

"Would that I might, my friend," answered Norman of Torn. "But hast thouthought on the consequences which surely would follow should I thus removeboth heart and head from the thing that I have built ?

"What suppose thou would result were Norman of Torn to turn his great bandof cut-throats, leaderless, upon England ? Hast thought on't, Father ?

"Wouldst thou draw a single breath in security if thou knew Edwild the Serfwere ranging unchecked through Derby ? Edwild, whose father was torn limbfrom limb upon the rack because he would not confess to killing a buck inthe new forest, a buck which fell before the arrow of another man; Edwild,whose mother was burned for witchcraft by Holy Church.

"And Horsan the Dane, Father. How thinkest thou the safety of the roadswould be for either rich or poor an I turned Horsan the Dane loose uponye ?

"And Pensilo, the Spanish Don ! A great captain, but a man absolutelywithout bowels of compassion. When first he joined us and saw our markupon the foreheads of our dead, wishing to out-Herod Herod, he marked theliving which fell into his hands with a red hot iron, branding a great Pupon each cheek and burning out the right eye completely. Wouldst like tofeel, Father, that Don Piedro Castro y Pensilo ranged free through forestand hill of England ?

"And Red Shandy, and the two Florys, and Peter the Hermit, and One EyeKanty, and Gropello, and Campanee, and Cobarth, and Mandecote, and thethousand others, each with a special hatred for some particular class orindividual, and all filled with the lust of blood and rapine and loot.

"No, Father, I may not go yet, for the England I have been taught to hate,I have learned to love, and I have it not in my heart to turn loose uponher fair breast the beasts of hell who know no law or order or decencyother than that which I enforce."

As Norman of Torn ceased speaking, the priest sat silent for many minutes.

"Thou hast indeed a grave responsibility, my son," he said at last. "Thoucanst not well go unless thou takest thy horde with thee out of England,but even that may be possible; who knows other than God ?"

"For my part" laughed the outlaw, "I be willing to leave it in His hands;which seems to be the way with Christians. When one would shirk aresponsibility, or explain an error, lo, one shoulders it upon the Lord."

"I fear, my son," said the priest, "that what seed of reverence I haveattempted to plant within thy breast hath borne poor fruit."

"That dependeth upon the viewpoint, Father; as I take not the Lord intopartnership in my successes it seemeth to me to be but of a mean and poorspirit to saddle my sorrows and perplexities upon Him. I may be wrong, forI am ill-versed in religious matters, but my conception of God andscapegoat be not that they are synonymous."

"Religion, my son, be a bootless subject for argument between friends,"replied the priest, "and further, there be that nearer my heart just nowwhich I would ask thee. I may offend, but thou know I do not mean to. Thequestion I would ask, is, dost wholly trust the old man whom thou callfather ?"

"I know of no treachery," replied the outlaw, "which he hath ever conceivedagainst me. Why ?"

"I ask because I have written to Simon de Montfort asking him to meet meand two others here upon an important matter. I have learned that heexpects to be at his Leicester castle, for a few days, within the week. Heis to notify me when he will come and I shall then send for thee and theold man of Torn; but it were as well, my son, that thou do not mention thismatter to thy father, nor let him know when thou come hither to the meetingthat De Montfort is to be present."

"As you say, Father," replied Norman of Torn. "I do not make head nor tailof thy wondrous intrigues, but that thou wish it done thus or so issufficient. I must be off to Torn now, so I bid thee farewell."

Until the following Spring, Norman of Torn continued to occupy himself withoccasional pillages against the royalists of the surrounding counties, andhis patrols so covered the public highways that it became a matter ofgrievous import to the King's party, for no one was safe in the districtwho even so much as sympathized with the King's cause, and many were thedead foreheads that bore the grim mark of the Devil of Torn.

Though he had never formally espoused the cause of the barons, it nowseemed a matter of little doubt but that, in any crisis, his grisly bannerwould be found on their side.

The long winter evenings within the castle of Torn were often spent inrough, wild carousals in the great hall where a thousand men might sit attable singing, fighting and drinking until the gray dawn stole in throughthe east windows, or Peter the Hermit, the fierce majordomo, tired of thedin and racket, came stalking into the chamber with drawn sword and laidupon the revellers with the flat of it to enforce the authority of hiscommands to disperse.

Norman of Torn and the old man seldom joined in these wild orgies, but whenminstrel, or troubadour, or storyteller wandered to his grim lair, theOutlaw of Torn would sit enjoying the break in the winter's dull monotonyto as late an hour as another; nor could any man of his great fierce hordeoutdrink their chief when he cared to indulge in the pleasures of the winecup. The only effect that liquor seemed to have upon him was to increasehis desire to fight, so that he was wont to pick needless quarrels and toresort to his sword for the slightest, or for no provocation at all. So,for this reason, he drank but seldom since he always regretted the thingshe did under the promptings of that other self which only could assert itsego when reason was threatened with submersion.

Often on these evenings, the company was entertained by stories from thewild, roving lives of its own members. Tales of adventure, love, war anddeath in every known corner of the world; and the ten captains told, each,his story of how he came to be of Torn; and thus, with fighting enough byday to keep them good humored, the winter passed, and spring came with theever wondrous miracle of awakening life, with soft zephyrs, warm rain, andsunny skies.

Through all the winter, Father Claude had been expecting to hear from Simonde Montfort, but not until now did he receive a message which told the goodpriest that his letter had missed the great baron and had followed himaround until he had but just received it. The message closed with thesewords:

"Any clew, however vague, which might lead nearer to a true knowledge ofthe fate of Prince Richard, we shall most gladly receive and give our bestattention. Therefore, if thou wilst find it convenient, we shall visitthee, good father, on the fifth day from today."

Spizo, the Spaniard, had seen De Montfort's man leave the note with FatherClaude and he had seen the priest hide it under a great bowl on his table,so that when the good father left his cottage, it was the matter of but amoment's work for Spizo to transfer the message from its hiding place tothe breast of his tunic. The fellow could not read, but he to whom he tookthe missive could, laboriously, decipher the Latin in which it was penned.

The old man of Torn fairly trembled with suppressed rage as the fullpurport of this letter flashed upon him. It had been years since he hadheard aught of the search for the little lost prince of England, and nowthat the period of his silence was drawing to a close, now that more andmore often opportunities were opening up to him to wreak the last shred ofhis terrible vengeance, the very thought of being thwarted at the finalmoment staggered his comprehension.

"On the fifth day," he repeated. "That is the day on which we were to ridesouth again. Well, we shall ride, and Simon de Montfort shall not talkwith thee, thou fool priest."

That same spring evening in the year 1264, a messenger drew rein before thewalls of Torn and, to the challenge of the watch, cried:

"A royal messenger from His Illustrious Majesty, Henry, by the grace ofGod, King of England, Lord of Ireland, Duke of Aquitaine, to Norman ofTorn, Open, in the name of the King !"

Norman of Torn directed that the King's messenger be admitted, and theknight was quickly ushered into the great hall of the castle.

The outlaw presently entered in full armor, with visor lowered.

The bearing of the King's officer was haughty and arrogant, as became a manof birth when dealing with a low born knave.

"His Majesty has deigned to address you, sirrah," he said, withdrawing aparchment from his breast. "And, as you doubtless cannot read, I will readthe King's commands to you."

"I can read," replied Norman of Torn, "whatever the King can write. Unlessit be," he added, "that the King writes no better than he rules."

The messenger scowled angrily, crying:

"It ill becomes such a low fellow to speak thus disrespectfully of ourgracious King. If he were less generous, he would have sent you a halterrather than this message which I bear."

"A bridle for thy tongue, my friend," replied Norman of Torn, "were inbetter taste than a halter for my neck. But come, let us see what the Kingwrites to his friend, the Outlaw of Torn."

Taking the parchment from the messenger, Norman of Torn read:

Henry, by Grace of God, King of England, Lord of Ireland, Duke ofAquitaine; to Norman of Torn:

Since it has been called to our notice that you be harassing and plunderingthe persons and property of our faithful lieges ---

We therefore, by virtue of the authority vested in us by Almighty God, docommand that you cease these nefarious practices ---

And further, through the gracious intercession of Her Majesty, QueenEleanor, we do offer you full pardon for all your past crimes ---

Provided, you repair at once to the town of Lewes, with all the fightingmen, your followers, prepared to protect the security of our person, andwage war upon those enemies of England, Simon de Montfort, Gilbert de Clareand their accomplices, who even now are collected to threaten and menaceour person and kingdom ---

Or, otherwise, shall you suffer death, by hanging, for your long unpunishedcrimes. Witnessed myself, at Lewes, on May the third, in the forty-eighthyear of our reign.

HENRY, REX.

"The closing paragraph be unfortunately worded," said Norman of Torn, "forbecause of it shall the King's messenger eat the King's message, and thustake back in his belly the answer of Norman of Torn." And crumpling theparchment in his hand, he advanced toward the royal emissary.

The knight whipped out his sword, but the Devil of Torn was even quicker,so that it seemed that the King's messenger had deliberately hurled hisweapon across the room, so quickly did the outlaw disarm him.

And then Norman of Torn took the man by the neck with one powerful handand, despite his struggles, and the beating of his mailed fists, bent himback upon the table, and there, forcing his teeth apart with the point ofhis sword, Norman of Torn rammed the King's message down the knight'sthroat; wax, parchment and all.

It was a crestfallen gentleman who rode forth from the castle of Torn ahalf hour later and spurred rapidly - in his head a more civil tongue.

When, two days later, he appeared before the King at Winchelsea andreported the outcome of his mission, Henry raged and stormed, swearing byall the saints in the calendar that Norman of Torn should hang for hiseffrontery before the snow flew again.

News of the fighting between the barons and the King's forces at Rochester,Battel and elsewhere reached the ears of Norman of Torn a few days afterthe coming of the King's message, but at the same time came other newswhich hastened his departure toward the south. This latter word was thatBertrade de Montfort and her mother, accompanied by Prince Philip, hadlanded at Dover, and that upon the same boat had come Peter of Colfax backto England -- the latter, doubtless reassured by the strong conviction,which held in the minds of all royalists at that time, of the certainty ofvictory for the royal arms in the impending conflict with the rebel barons.

Norman of Torn had determined that he would see Bertrade de Montfort onceagain, and clear his conscience by a frank avowal of his identity. He knewwhat the result must be. His experience with Joan de Tany had taught himthat. But the fine sense of chivalry which ever dominated all his actswhere the happiness or honor of women were concerned urged him to givehimself over as a sacrifice upon the altar of a woman's pride, that itmight be she who spurned and rejected; for, as it must appear now, it hadbeen he whose love had grown cold. It was a bitter thing to contemplate,for not alone would the mighty pride of the man be lacerated, but a greatlove.

Two days before the start of the march, Spizo, the Spaniard, reported tothe old man of Torn that he had overheard Father Claude ask Norman of Tornto come with his father to the priest's cottage the morning of the march tomeet Simon de Montfort upon an important matter, but what the nature of thething was the priest did not reveal to the outlaw.

This report seemed to please the little, grim, gray old man more than aughthe had heard in several days; for it made it apparent that the priest hadnot as yet divulged the tenor of his conjecture to the Outlaw of Torn.

On the evening of the day preceding that set for the march south, a little,wiry figure, grim and gray, entered the cottage of Father Claude. No manknows what words passed between the good priest and his visitor nor thedetails of what befell within the four walls of the little cottage thatnight; but some half hour only elapsed before the little, grim, gray manemerged from the darkened interior and hastened upward upon the rocky trailinto the hills, a cold smile of satisfaction on his lips.

The castle of Torn was filled with the rush and rattle of preparation earlythe following morning, for by eight o'clock the column was to march. Thecourtyard was filled with hurrying squires and lackeys. War horses werebeing groomed and caparisoned; sumpter beasts, snubbed to great posts, werebeing laden with the tents, bedding, and belongings of the men; while thosealready packed were wandering loose among the other animals and men. Therewas squealing, biting, kicking, and cursing as animals fouled one anotherwith their loads, or brushed against some tethered war horse.

Squires were running hither and thither, or aiding their masters to donarmor, lacing helm to hauberk, tying the points of ailette, coude, androndel; buckling cuisse and jambe to thigh and leg. The open forges ofarmorer and smithy smoked and hissed, and the din of hammer on anvil roseabove the thousand lesser noises of the castle courts, the shouting ofcommands, the rattle of steel, the ringing of iron hoof on stone flags, asthese artificers hastened, sweating and cursing, through the eleventh hourrepairs to armor, lance and sword, or to reset a shoe upon a refractory,plunging beast.

Finally the captains came, armored cap-a-pie, and with them some semblanceof order and quiet out of chaos and bedlam. First the sumpter beasts, allloaded now, were driven, with a strong escort, to the downs below thecastle and there held to await the column. Then, one by one, the companieswere formed and marched out beneath fluttering pennon and waving banner tothe martial strains of bugle and trumpet.

Last of all came the catapults, those great engines of destruction whichhurled two hundred pound boulders with mighty force against the walls ofbeleaguered castles.

And after all had passed through the great gates, Norman of Torn and thelittle old man walked side by side from the castle building and mountedtheir chargers held by two squires in the center of the courtyard.

Below, on the downs, the column was forming in marching order, and as thetwo rode out to join it, the little old man turned to Norman of Torn,saying,

"I had almost forgot a message I have for you, my son. Father Claude sentword last evening that he had been called suddenly south, and that someappointment you had with him must therefore be deferred until later. Hesaid that you would understand." The old man eyed his companion narrowlythrough the eye slit in his helm.

"'Tis passing strange," said Norman of Torn but that was his only comment.And so they joined the column which moved slowly down toward the valley andas they passed the cottage of Father Claude, Norman of Torn saw that thedoor was closed and that there was no sign of life about the place. A waveof melancholy passed over him, for the deserted aspect of the littleflower-hedged cote seemed dismally prophetic of a near future without thebeaming, jovial face of his friend and adviser.

Scarcely had the horde of Torn passed out of sight down the east edge ofthe valley ere a party of richly dressed knights, coming from the south byanother road along the west bank of the river, crossed over and drew reinbefore the cottage of Father Claude.

As their hails were unanswered, one of the party dismounted to enter thebuilding.

"Have a care, My Lord," cried his companion. "This be over-close to theCastle Torn and there may easily be more treachery than truth in themessage which called thee thither."

"Fear not," replied Simon de Montfort, "the Devil of Torn hath no quarrelwith me." Striding up the little path, he knocked loudly on the door.Receiving no reply, he pushed it open and stepped into the dim light of theinterior. There he found his host, the good father Claude, stretched uponhis back on the floor, the breast of his priestly robes dark with dried andclotted blood.

Turning again to the door, De Montfort summoned a couple of his companions.

"The secret of the little lost prince of England be a dangerous burden fora man to carry," he said. "But this convinces me more than any words thepriest might have uttered that the abductor be still in England, andpossibly Prince Richard also."

A search of the cottage revealed the fact that it had been ransackedthoroughly by the assassin. The contents of drawer and box littered everyroom, though that the object was not rich plunder was evidenced by manypieces of jewelry and money which remained untouched.

"The true object lies here," said De Montfort, pointing to the open hearthupon which lay the charred remains of many papers and documents. "Allwritten evidence has been destroyed, but hold what lieth here beneath thetable ?" and, stooping, the Earl of Leicester picked up a sheet ofparchment on which a letter had been commenced. It was addressed to him,and he read it aloud:

Lest some unforeseen chance should prevent the accomplishment of ourmeeting, My Lord Earl, I send thee this by one who knoweth not either itscontents or the suspicions which I will narrate herein.

He who bareth this letter, I truly believe to be the lost Prince Richard.Question him closely, My Lord, and I know that thou wilt be as positive asI.

Of his past, thou know nearly as much as I, though thou may not know thewondrous chivalry and true nobility of character of him men call ---

Here the letter stopped, evidently cut short by the dagger of the assassin.

"Mon Dieu ! The damnable luck !" cried De Montfort, "but a second more andthe name we have sought for twenty years would have been writ. Didst eversee such hellish chance as plays into the hand of the fiend incarnate sincethat long gone day when his sword pierced the heart of Lady Maud by thepostern gate beside the Thames ? The Devil himself must watch o'er him.

"There be naught more we can do here," he continued. "I should have beenon my way to Fletching hours since. Come, my gentlemen, we will ride southby way of Leicester and have the good Fathers there look to the decentburial of this holy man."

The party mounted and rode rapidly away. Noon found them at Leicester, andthree days later, they rode into the baronial camp at Fletching.

At almost the same hour, the monks of the Abbey of Leicester performed thelast rites of Holy Church for the peace of the soul of Father Claude andconsigned his clay to the churchyard.

And thus another innocent victim of an insatiable hate and vengeance whichhad been born in the King's armory twenty years before passed from the eyesof men.